Greetings one and all!

So, predictably, the Alternative Vote, the one chance that us Brits will have to change our outdated and unfair electoral system in a generation, has failed, undermined by a lackluster "Vote Yes" campaign, some cynical, misleading and nasty campaigning from the "No" camp, and the fact that the whole country now hates Nick Clegg. In fact, had the aforementioned Deputy PM really wanted it to pass, he should have gone around the country campaigning for First Past the Post. The result would no doubt have been a Yes landslide. Instead, we keep a stupid system that favours the Tories and Labour, the former even more so now that their plans to redraw the electoral map can go ahead. Oh well...

Then, of course, there was the Royal Wedding, between Prince William and the "lower class" Kate Middleton. Such an event, yet I slept through it, something I apparently should be grateful for, as it involved such levels of sycophancy and talk of hats that I probably would have topped myself. Sometimes alcoholism has its plus points.

Luckily, I have more edifying things to interest and amuse me, such as Gerard Malanga and Victor Bokris' Up-Tight; The Velvet Underground Story. Malanga was one of the dancers in the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, the multimedia show that Andy Warhol put together to accompany the Velvets in the early days when they had Nico as "chanteuse". Poorly edited, the book nonetheless gives some interesting insight into the circus that surrounded this most important of rock bands (the best ever?), from the Warhol-mania of the first two years, through the lackluster promotion by MGM, the departures of Nico, Warhol and guitarist/bassist/viola player, and musical genius, John Cale, to the band's ultimate demise in a cloud of paranoia and drug abuse, usually involving the egocentric other genius of the whole enterprise, Lou Reed. The main protagonists' complex personalities and interactions are laid out in much detail and, whilst there will always be something frustrating about how things panned out, for the musicians themselves as well as fans like me, Up-Tight essentially serves as reminder -were it needed- of how innovative, exciting and creative The Velvet Underground really was.

Hip-hop is not usually a genre I have much time for. Obviously, the prevalent (and generally unchallenged) homophobia, sexism and crass glorification of materialism are massive turnoffs for me, and people can say whatever they like about Eminem's supposed "talent", the fact that he's written songs about physically attacking gay people and calling us "faggots" means he can jump up his own arse and die as far as I'm concerned. But beyond such ethical matters, there's also a sense that rap and hip-hop have lost their mojo, the music becoming shiny and over-produced, the lyrics less interesting the more they focus on cars and ass over political issues. The days of Nas' superb Illmatic album seem far away now.

Which is why legendary, lamented Houston-based producer DJ Screw remains such a truly essential figure, eleven years after his untimely passing. Screw invented a new way of approaching hip-hop, taking existing tracks and slowing them down, cutting them up and reassembling them as off-kilter reflections of the originals, often highlighting the emotive power or humourous undercurrents of the source materials.

Pat Maherr, discovered by me last year under his Indignant Senility moniker, is obviously a keen follower of the DJ Screw style, and gives a wonderful demonstration of the possibilities of this approach -dubbed Chopped and Screwed- on the debut album of his Expressway Yo-Yo Dieting project, Bubblethug (Weird Forest, 2010). The album surges out of the speakers from the get-go, the first of 13 untitled ("Unknown") tracks leaping forwards with a lopsided gait and awkward brazenness. Ugly, untidy beats accompany a voice so slowed-down as to be rendered unintelligible, an untethered moan that is almost hilarious as the other core elements of the track -a shimmer of electronic synths, some ghostly backing vocals- attempt to bring coherence to the unsightly (but hypnotic) mess. In 6 minutes and 3 seconds, Maherr pretty much rewrites the rules of hip-hop, destroying the genre's macho swagger and turning it into something rawer, more unhinged from material concerns and therefore both primordial and futuristic.

Bubblethug is therefore a confusing slab of modern pop, uneasily ghosting between genres, always hip-hop at its core, but unremittingly dark, as the tortured vocals and minimalist music pervert the joviality of the album's parent genre. On the third track, the abrasive, disjointed percussion recalls the metallic crunch of early Einsturzende Neubauten or Test Dept., with track 4 also following a similar industrial path, with an opening burst of tremelo-ed noise that wouldn't sound out of place on a Skullflower album circa Orange Canyon Mind or Taste the Blood of the Deceiver, which leads intot he kind of noisy pounding groove familiar to most SPK fans. By track 8, Maherr whittles down the grooves completely, leaving a shapeless post-industrial ambience, before launching a messed-up, motorik form of driving-krautrock-meets-hardcore-rap on the 9th track, joining the dots between house, ambient techno and pure, krunky hip-hop.

At hip-hop's core are synths, beats and vocals. By untethering them from each other, Maherr allows these parts to dissolve into a post-noise miasma, honing in on the gloomy core of the tracks he's fucking up whilst freeing up the genre to incorporate fresh ideas. Whilst, like Indignant Senility's Plays Wagner, Bubblethug is overlong, it hits more often than it misses and Maherr has managed once again to create something fresh, exciting and rather peculiar.

A word I've seen used to describe such experimental manipulations of hip-hop is "underwater", and it would be equally apt if applied to the meandering drone of Geoff Mullen's wonderful Bongo Closet (Type, 2010). It's an odd title for an album of haunting, whispy, electronic drone, but, as one reviewer noted, you don't have to have bongos in your bongo closet. It also suggests hidden, forgotten instrumentation, and Mullen's elusive use of percussive elements illustrates this rather mysterious approach to sound sculpture. Most of the album, straight from the opening track, doesn't so much advance as drift, weightlessly, with quiet ebbs and flows evoking the best of Thomas Koener, always hanging at the edge of perception as deep bass notes rumble towards your guts and occasional wafts of synth patterns edge into focus before sliding away into the digital haze.

The possible exception is the second track, on which the album's title is given an ironic twist through sub-aquatic percussion that seems to seep into the mix from very far away whilst echoey guitar snippets and occasional flutters of electronics dart and surge like butterflies fluttering around your head. It's a sort of languid take on the motorik krautrock of Neu, but performed with the ethos of ambient kosmische pioneers Cluster, pulsating and oblique. In the end, the album's closest cousin is probably D'Agostino/Foxx/Jansen's classic A Secret Life, sharing that album's delicate sense of urban alienation and detached melancholia. There will always be something vaguely insubstantial to such deliberately vague and transluscent music, but the hidden sensitivities are wonderfully comforting, particularly in the deep of a city night.

As underground music has exploded in a myriad of directions, one rather reliable constant has been the enthusiasm for bass music, from the hugely successful uber-throbbing dancefloor music that is dubstep, to the pop-reggae crossovers that have emerged, mostly from the USA, in the wake of David Keenan's heralding of the hypnagogic pop epoch. In this regards, husband-and-wife duo Peaking Lights are not really plowing a novel furrow on 936 (Not Not Fun, 2011), coming on the back of labelmates Sun Araw and Pocahaunted's success, but it is one of the better example of how underground electronic pop-rock can be threaded into dub and still be accessible, tuneful and hi-energy (ok, not that energetic, this is languid stuff, but it's not as drawn-out as most dub).

The considerable strength of 936 is the duo's songwriting craft, which probably exceeds that of Pocahaunted, even at that band's Island Diamonds pomp. Tracks like "Amazing and Wonderful" and "Birds of Paradise" have a verve, vim and drive that is incredibly infectious, hooking you from the get-go and swimming through your system like cold tonic on a warm day. The balance between the fat bass lines and the synth/guitar melodies is pitch-perfect, whilst Indra Dunis' dreamy voice is used to perfection. There are also some wonderful drum machine beats, notably on "Amazing and Wonderful", which glides along like a wave on a sandy beach. Compared to the deliberately woozy dub-pop of many of their contemporaries, Peaking Lights keep things energetic and anchored in the Slits/PiL tradition that birthed the marriage of dub and western music. An accomplished album.

Fucking hell - I really, truly, deeply, unconditionally, fucking LOVE The Rita!! Ok, so that's a bit mad, but it's hardly my fault given the overwhelming quality of just about everything Sam McKinley does.

The Voyage of The Decima MAS (Troniks, 2009) may be his most extraordinary statement yet, the culmination and sublimation of everything that has thus far been accomplished in the field of Harsh Noise Walls. If giallo film scores and underwater recordings of sharks provided excellent sources to be manipulated by The Rita's devillish hand and turned into walls of unending saturation, on The Voyage of The Decima MAS, he has found his best material yet, as he uses recordings of -wait for it- snorkelling (!) to deliver something so outlandish it could just about represent the apex of this noise sub-genre. I mean, just consider it - this surely represents a stroke of genius on McKinley's apart, something that is apparent from the first second. The album launches with a traditional burst of unmoving, hugely saturated and crackling white noise, but almost immediately evolves into the furious rumble and burble of bubbles whistling through a snorkel. Amplified to the extreme, these sounds become part of the wall of sound, bass-heavy and abrasive, but much more dynamic than anything on A Thousand Dead Gods or Bodies Bear Traces of Carnal Violence. The listener is not so much assaulted as -and surely this is the ultimate aim of most HNW?- submerged, plunged into the sound as if into a vast, turbulent ocean.

Rest assured, The Voyage of The Decima MAS is as monolithic, harsh and implacable as anything done in the world of harsh noise, with the familiar grittiness so frequently encountered in American noise, but the sudden eruptions of swirling, volcanic water sounds gives it a sense of drama (at times you can feel like you're drowning, such is the psychological impact of the sounds) and impetus that elevates it above most of its contemporaries. McKinley's approach is cerebral, an exploration of how a genre as alienating as noise can evoke emotions beyond the traditional anger, viciousness or brutality associated with it, and plunges it (almost literally) into a consideration of nature versus technology, the effect pedal against the roaring ocean. It may just be the best-ever harsh noise album, certainly close, and definitely one that elevates The Rita to similar status -in my eyes- as Merzbow, Hijokaidan and Werewolf Jerusalem.

Hmm, with the possible exception of Peaking Lights, I seem to have gone for a sub-aquatic theme this month. Curious...

Decidely NOT watery was the wonderful Fred Frith concert I attended on April 28th at the now-ubiquitous in my life Cafe Oto. Frith, formerly of Henry Cow and Art Bears, and who released one of the world's greatest albums of guitar improv, Guitar Solos (1974), delivered one of the best concerts I've ever seen and, coming so soon after Keiji Haino's equally wondrous two-day residency a few weeks earlier, I'm beginning to think that Oto, for all the falafel-and-ginger-beer propensities of its crowd, can do no wrong.

Like Haino, Frith's first set was a solo exploration of the extreme possibilities of electric guitar, as he used a variety of tools, from spinning copper plates to chain necklaces, plus his faithful effects pedals and speedy fingers, to extract a wonderful array of sounds, from punkish sturm und drang to elegant, deeply emotive melodic motifs. It was fascinating to watch, and deeply moving.

For the second set, he was joined by drummer Roger Turner, and there was a sense of gleeful exploration as the two men set about improvising with a delight and humour too often missing from such explorations. Both carried on the exercise of using weird utensils on their instruments, but never for weirdness' sake alone, and never forgot to rock out and deliver tangible riffs and melodies for the audience's delectation.

For the third piece, more abstract, Frith joined forces with genius saxophonist John Butcherb and cellist Hannah Marshall, before Turner returned for a grandiose, powerful finale. These two performances were certainly more challenging than the first two, and perhaps a tad too cerebral in comparison to the raw energy and humour of the first half, but you could not but admire the sheer talent and virtuosity they all displayed. Another fantastic demonstration of the power of experimental music in the live setting, once again sold-out, as if to prove there is hope for avant-garde art in these dark, lowbrow times.

In movies, two films I saw last month were worthy of note, being stand-out examples of the portrayal of homosexuality in film, from opposite ends of the struggle for equal rights.

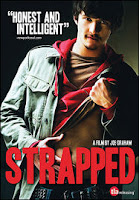

Released last year, Strapped is an excellent little indie film written and directed by Joseph Graham, which takes place solely within a single apartment building. Hunky young actor Ben Bonenfant plays a veteran hustler who services a john, helping him come to terms with his sexuality in the process, but then finds himself unable to find a way out of the building, leading to more and more encounters with the sad, the fucked-up, the lonely, the old and the repressed of the gay world. It's a familiar theme in gay cinema, is hustling, but in Strapped it is approached from a novel angle, as Bonenfant's character, whilst providing temporary or lasting solace to others, starts to analyse his own life and his own purgatory. The dialogue is smart and intense, and the various characters, whilst all archetypes, have a depth and emotion to them that is testament to Graham's skill as a writer.

As novel as it it may be, Strapped is nonetheless a product of a world where homosexuality, whilst not always completely accepted, is a legally recognised sexual orientation and lifestyle; and was released in the relatively open-minded 2010s. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Basil Dearden's Victim, released in 1962, came out at a time when sexual intercourse between two men or two women was illegal in the United Kingdom, and punishable with a prison sentence. Its very creation was an act of bravery and, as expected, it was wholly controversial, though now cited as one of the factors that led to decriminalisation in 1967. The late, great, nay, magnificent, Dirk Bogarde plays a successful, married, QC names Farr, whose young gay friend, with whom he had a platonic but affectionate relationship, commits suicide after being blackmailed over his relationship with Farr. When Farr attempts to take on the blackmailers, his own homosexual past, and the hostility of conservative society, not to mention the blackmailers themselves, threaten to jeopardise his career and the facade of "normal" life he's built up. In terms of narrative and photography, Victim is pretty standard of its time, and hardly ground-breaking, but the fact that it tackles such a then-taboo subject head-on, not to mention a marvelous central turn by Bogarde, make it one of the most important films ever to deal with gay issues. It doesn't flinch from portraying homosexuality as natural, and gay men as the unfortunate victims of repressive law and evil blackmailers. A brave and stirring film, one that all gay men and women should see, especially as it highlights the struggles and anguish our forbears had to face.

Much as with Cafe Oto, I finally put paid to a glaring omission from my East End cultural landscape by finally going to the wonderful Whitechapel Gallery (website here: http://www.whitechapelgallery.org/home). I cannot recommend this -usually 100% free- gallery enough, as it combines all kinds of forms of artistic expression and above all gives voice (and canvas and space) to little-known and emerging artists. However, on the day I went I was lucky to visit their extensive retrospective of the 30-year career of photographer Paul Graham.

His earliest works from the eighties, i.e. Thatcher's Britian (the show is chronological), were notable for their political nature. In "The Great North Road", he explores the UK's north-south divide, and social inequality through photos taken along the A1, from "comfortable" north London to Edinburgh via sleepy former industrial cities and rundown backwaters. His pictures have the forlorn weariness of an American road movie a la Broken Flowers or Paris Texas, and shine an unusual light on England's battered roadsides. In "Beyond Caring", he takes his wide, cinematic approach to dole offices, filming those miserable antechambers of poverty and the unfortunate souls who had to trek into them every day in a desperate often vain attempt to find work. The grubby offices and haggard-looking people in them serve as an uncomfortable indictment of the Tory party's ghastly social policies. Given the way they're once again taking the knife to public services and jobs in 2011, "Beyond Caring" is unfortunately still very relevant, although the beauty of each picture's composition goes some way towards alleviating that sense of frustration.

In the 90s, Graham's pictures would become more abstract and poetic, as opposed to overtly political, as demonstrated in his series on Japan, "Empty Heaven", which juxtaposed images of traditional Japanese things like geishas and ceremonies with urban decay and modernity. Less demonstrative, this opposition of images, in bright, lurid coulour, leaves an impression of ambiguity, and even suspense. In "End of an Age", young people in an anonymous city at the turn of this century are photographed in close up, their expressions once again ambiguous as they approach the uncertain future of the new millenium, with a deeply melancholy vbe permeating throughout. Best of all, in "Ceasefire", Graham uses gorgoeus pictures of grey skies, taken in Northern Ireland, to illustrate the frustration and uneasiness of yet another lull in the Troubles, this time in 1994. As history has shown, it would be tragically only a temporary reprieve.

By the last decade, Graham's ambition had grown even greater, and the last series, "a shimmer of possibility" combined the best of his earlier "social commentary" period with the sense of intimacy found in "End of an Age". He travelled the USA, photographing the multi-faceted aspects of American society, from crippling poverty to towering, modern cities, stopping to take small series focusing on particular individuals, as if trying to get more intimate with and close to his subjects' lives. The separation created by the camera of course creates an unavoidable barrier, meaning such closeness is only a vague possibility, and this dynamic creates real drama, and poetry.

Paul Graham was a wonderful discovery for me, and I heartily recommend art lovers visit the Whitechapel before the exhibition ends.

So ends another monthly musing. Peace!

- J Phimiser

No comments:

Post a Comment